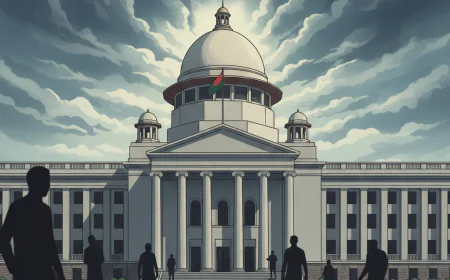

A Landmark Agreement Between India and Pakistan

More than six decades after its signing, the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) continues to serve as a rare example of successful water diplomacy between two historically adversarial neighbors—India and Pakistan. Signed on September 19, 1960, in Karachi, the treaty has withstood the test of time, surviving wars, military standoffs, and periods of diplomatic breakdown between the two South Asian nations.

The treaty was the result of prolonged negotiations that lasted almost nine years. Brokered by the World Bank (then the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development), the agreement was signed by Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Pakistani President Ayub Khan, and W.A.B. Iliff of the World Bank. It aimed to provide a fair and peaceful resolution to a potentially volatile dispute over the waters of the Indus River system that emerged after the Partition of British India in 1947.

The partition left the headworks of major rivers—such as the Ravi and Sutlej—within Indian territory, while their waters flowed into Pakistan. This geographical reality led to early conflicts over water access, especially as agriculture was (and remains) the economic backbone of both countries. In 1948, India briefly cut off water supply to some Pakistani regions, further escalating tensions and prompting Pakistan to seek international mediation.

What followed was a long and complex negotiation process led by David Lilienthal and later Eugene Black of the World Bank, who helped broker discussions that ultimately led to the formation of the Indus Waters Treaty.

Key Provisions of the Treaty

The treaty divides the six rivers of the Indus system between the two countries:

- India received exclusive rights to the Eastern Rivers: Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej.

- Pakistan was granted exclusive use of the Western Rivers: Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab.

While India is allowed to use the Western Rivers for non-consumptive purposes such as irrigation, hydropower, and transport, any project on these rivers must follow strict design and notification criteria to ensure they do not significantly impact the flow into Pakistan.

To manage the agreement, the treaty also established the Permanent Indus Commission, consisting of one commissioner from each country. The commission meets regularly to exchange data, address technical concerns, and resolve disputes. The mechanism has played a key role in defusing tensions over the years, even when diplomatic relations have been otherwise frozen.

Remarkably, the Indus Waters Treaty has held firm during major conflicts between India and Pakistan, including the wars of 1965, 1971, and the Kargil conflict in 1999. Even during the heightened tensions following the 2016 Uri attack and the 2019 Pulwama terror attack, both nations continued to uphold the terms of the treaty, though rhetoric around possible revocation or renegotiation intensified.

India has in recent years signaled its intent to maximize the use of its share of water, particularly from the Eastern Rivers, and accelerate hydropower projects in Jammu and Kashmir. Pakistan has raised objections to some of these initiatives, fearing they could alter the flow of water into its territory. Several of these disputes have been taken up through the treaty’s dispute resolution mechanisms, including neutral expert mediation and arbitration under the treaty’s framework.

Today, the treaty faces new challenges beyond geopolitics. Climate change, glacial retreat, altered rainfall patterns, and increased water demand are putting immense pressure on the river system. Both India and Pakistan face mounting domestic water crises, prompting calls for better water management, updated infrastructure, and even revisiting some aspects of the treaty.

Environmentalists and water experts argue that while the IWT has succeeded in conflict prevention, it falls short in addressing modern sustainability challenges. Critics also point out that the treaty lacks provisions for groundwater management and basin-wide environmental protection—issues that were less understood in the 1960s.

Despite its limitations, the Indus Waters Treaty is widely regarded as one of the most successful water-sharing agreements in the world. It is frequently cited in international forums as a model of transboundary water cooperation.

In a region often marked by hostility and mistrust, the treaty serves as a crucial example of how diplomacy, backed by strong institutional mechanisms, can ensure the peaceful sharing of vital natural resources. As the world grapples with increasing water stress, the Indus Waters Treaty stands as a beacon of pragmatic diplomacy, offering valuable lessons for other nations facing similar challenges.

More than 64 years after its inception, the Indus Waters Treaty remains a symbol of what is possible even in the most difficult bilateral relationships. While new realities demand that both countries work together to address emerging threats to water security, the treaty's core principles—cooperation, communication, and mutual benefit—remain as relevant today as they were in 1960.

Whether it will continue to hold in the face of 21st-century pressures depends not only on the strength of the treaty itself but on the political will of India and Pakistan to preserve and adapt this landmark agreement for generations to come.