Liberation War Supreme, Yet July Uprising Was Unprecedented: Ali Riaz

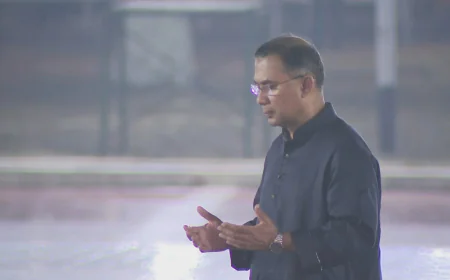

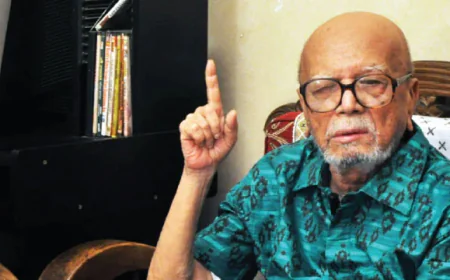

The July Uprising is often described as a “second independence,” but Ali Riaz, vice-chairman of the National Consensus Commission, firmly rejects the label and does not even consider it a revolution.

He reaffirmed that while the Liberation War of 1971 remains the defining moment in Bangladesh’s history, the July Uprising of 2024 was “unprecedented” in its scale and nature.

Riaz, a professor of politics and government at Illinois State University, made the remarks during an interview on bdnews24.com’s flagship discussion programme Inside Out. He had previously served as the head of the interim government’s Constitutional Reform Commission.

Rejecting the claim that Aug 5 marked a “second independence,” Riaz said: “Some have called it that, but I disagree. Personally, I say no — 1971 stands above everything else.”

Though many view the July Uprising as revolutionary, Riaz insists on calling it a mass uprising, not a revolution.

“There’s no need to deny or replace the Liberation War. But we must also acknowledge that what happened in 2024 was unprecedented — and we arrived there through a continuity of history,” he said.

NO PLAN TO ‘EXCLUDE 1971’

In a recent dialogue with the Consensus Commission, the Gono Forum expressed concern that proposed constitutional reforms might “exclude” the Liberation War. Riaz dismissed the worry as a misunderstanding.

“If we wanted to exclude 1971, then what would become of the Constitution’s core values — equality, human dignity, and social justice?” he said. “Nothing is being replaced.”

He emphasised that while political parties are entitled to interpret reforms from their own perspectives, there is no intent to sideline 1971.

“The goal is not to diminish the significance of the Liberation War, nor to underplay 2024. But drawing direct comparisons weakens both.”

He added that the 2024 uprising differed significantly from the 1990 movement, as it stemmed from a desire to reshape the state structure, not just remove a regime.

REFORM TALKS: BROAD AGREEMENT, DIVERGING DETAILS

The National Consensus Commission, led by Chief Advisor Muhammad Yunus, is currently conducting dialogue with political parties on reforms to the Constitution, electoral laws, public administration, and the judiciary.

On Inside Out, Riaz revealed that the first phase of discussions is nearing completion, and that a consensus document will be drafted after the second round.

“There is consensus on many issues at the policy level,” he said. “Nearly all political parties agree that institutional reforms are necessary — covering the Constitution, electoral process, the Anti-Corruption Commission, the judiciary, and public administration.”

However, differences remain on how to implement those reforms.

For instance, on judicial independence, parties agree in principle but propose differing methods.

On Article 70 of the Constitution, which strips MPs of their seats if they vote against party lines, Riaz said there is strong consensus that the provision must be revised.

“To give MPs greater freedom, Article 70 needs to be changed — and there is broad agreement on that.”

He also pointed to common ground on the need for more effective and autonomous functioning of the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC).

“Everyone acknowledges that the ACC must be made more independent and proactive. Electoral reform also enjoys broad support.”

While divergences in approach remain, Riaz said such differences are natural given the ideological diversity among parties.

“Despite varying ideologies, there is a shared recognition that reforms are essential — and that’s where the common ground lies.”

‘MISUNDERSTANDING’ PLURALISM

The reform commissions’ reports proposed changes to the state’s foundational principles, the official name of the country, and the parliamentary framework.

While the current Constitution enshrines nationalism, socialism, democracy, and secularism as state principles, the commission has recommended replacing them with equality, human dignity, social justice, pluralism, and democracy.

Among these, the inclusion of “pluralism” has drawn objections from religion-based political parties, who claim the term conflicts with Islamic values.

Commenting on the matter, Riaz said: “There appears to be a misunderstanding here. Many seem to view this term strictly through a religious lens, with some interpreting pluralism as being opposed to monotheism.

“But the Constitutional Reform Commission did not approach it from that angle.”

He noted that the global understanding of secularism has significantly evolved over the decades.

“Even in Bangladesh, we’ve seen that the notion of secularism has sometimes caused confusion,” he said.

Riaz added, “We are in fact a pluralistic society—ethnic, linguistic and social diversity exists here. The question is whether we are bringing everyone under equal security, equality and dignity. That is why we mentioned pluralism.”

He said the issues are being reviewed in light of discussions held with the political parties.

“Many political parties we’ve spoken to said they understand the rationale. But they also highlight our current social and political realities,” the political analyst added.

“We’re not living in an ideal society. Some have suggested that even if the essence is retained, the terminology might be reconsidered.

“We are listening to those suggestions, and the discussions are in progress.”

The reform commission’s chief justified the proposed removal of “secularism” from the Constitution by arguing that both its academic meaning and practical application have shifted.

“There is now an effort to address broader social inequalities, which is not limited to religious neutrality,” he said.

He pointed out that Bangladesh’s Constitution has recognised “secularism” as a state ideal for only 17 years in total, meaning it has been absent for the majority of the country’s history.

“The kinds of challenges often associated with its absence were also present when it was in place,” he said.

“We tend to focus only on religion when considering the protection of minorities, but many are marginalised in other social ways as well.

“So the idea of dropping secularism stems from the need to expand the concept and make it more inclusive.”

Riaz also noted that the four original principles adopted in 1972 — including secularism — were, in fact, introduced by a single political party.

According to him, “Before the Constituent Assembly committee began drafting the Constitution, the Awami League’s working committee decided those would be the state’s guiding principles.

“But the Liberation War was not fought by one party alone. It was a people’s war involving numerous forces, individuals, and political parties.”

He said the Constituent Assembly in 1972 failed to fully reflect those broader voices.

“Among the four founding principles, only secularism is universally applicable. The inclusion of ‘Bengali nationalism’ ignores the contributions of non-Bengali communities in the war.

“Considering all these factors, it was viewed as a package,” he added.

Riaz emphasised that three of the newly proposed principles — equality, human dignity, and social justice — are drawn directly from the Proclamation of Independence of Bangladesh.

“This was the founding promise of the Bangladeshi state. Our goal is to return to the spirit of 1971,” he said.