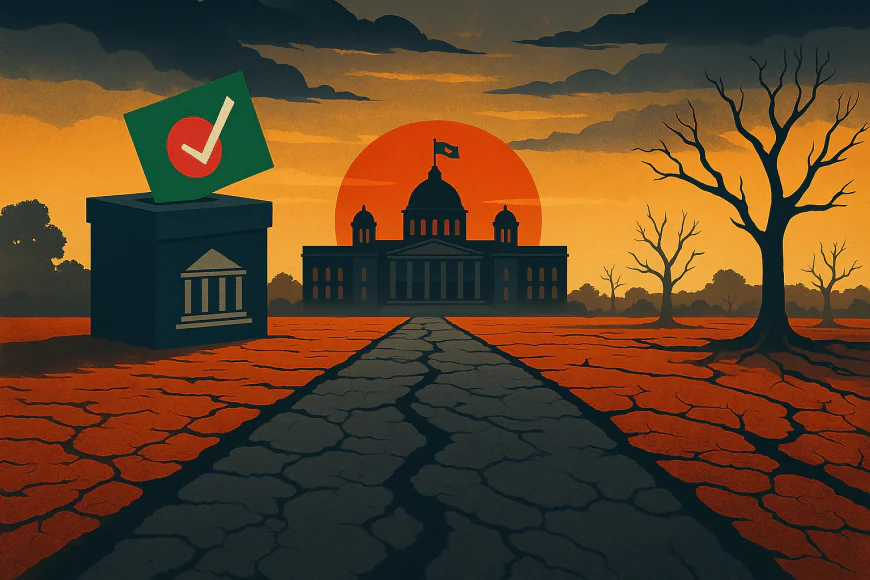

Postponing the Vote Undermines Democracy

By all accounts, the announcement by interim Adviser Muhammad Yunus that Bangladesh’s next general elections will be held in April 2026 is a defining political development. It comes at a time when the country is navigating a delicate transition from authoritarian dominance to what many hope will be a reinvigorated democratic future. However, despite the optimism that initially greeted the formation of the caretaker government, this extended timeline for elections risks undermining both public confidence and the very legitimacy the interim administration seeks to restore.

Public sentiment across Bangladesh is clear and compelling: the people want elections, and they want them soon. In fact, surveys from multiple independent sources indicate that a majority of citizens would prefer elections by the end of 2025 at the latest. A nationwide study by Innovision Consulting revealed that 58% of respondents wanted elections before the end of this year. Another by VOA Bangla indicated that over 61% of citizens believe elections should be held within a year.

This growing urgency is not a mere expression of political impatience. Rather, it reflects deep-seated anxiety about the country’s economic conditions, the loss of democratic representation, and the slow pace of institutional reform. After enduring years of political suppression and growing disenfranchisement, Bangladeshis are demanding more than administrative stability—they are demanding accountability.

Perhaps the most pressing driver of this demand for elections is the economy. According to the “People’s Election Pulse” survey, nearly 70% of respondents listed price hikes and inflation as their number one concern, followed closely by concerns about law and order and unemployment. These numbers speak to a population that is struggling to cope with day-to-day survival, let alone think about a future governed by promises of reform.

And this is where the government’s extended timeline feels particularly out of touch. Bangladesh’s economy is at a critical juncture. Prolonged political uncertainty only worsens investor hesitancy, deepens market instability, and accelerates public frustration. Without an elected government empowered to implement long-term economic policies, the caretaker administration’s reformist agenda risks becoming a well-intentioned but ineffectual stopgap.

There is no denying that the Yunus-led interim government has introduced important conversations around judicial independence, electoral transparency, and decentralization of power. But reforms are not enough in themselves—they must be timely, inclusive, and rooted in legitimacy. And that legitimacy can only come from a mandate granted by the people through free and fair elections.

Delaying polls until April 2026, even under the guise of completing necessary reforms, risks alienating the very public the government claims to serve. Citizens are increasingly skeptical about how much genuine transformation can occur without electoral accountability. Moreover, history warns us that transitional regimes, even if formed with the noblest of intentions, tend to overstay their welcome if not bound by clear timelines and legal safeguards.

Another argument that undermines the need for a late 2026 election is the readiness of Bangladesh’s political actors. Despite years of suppression, the opposition has shown signs of resurgence. The BNP is actively organizing, Jamaat-e-Islami has re-entered the political discourse, and new players like the student-led National Citizen Party are energizing a new generation of voters. Public engagement in political conversations has notably increased, and digital platforms are abuzz with electoral discourse.

In other words, the conditions for elections are not only ripening—they are demanding to be recognized. The longer the government delays, the more it risks being seen not as a transitional authority, but as an unelected power structure out of step with public will.

Democracy is not merely a constitutional formality; it is a covenant between the people and those who govern. The 2024 transitional moment gave Bangladesh an opportunity to heal from past political wounds. The appointment of Yunus as interim Adviser was seen as a reset button—an independent figure known for integrity, placed at the helm to usher in credible, inclusive elections.

But that promise is fragile. Prolonging the election timeline without clear public backing threatens to break the trust that citizens placed in this process. Even if reforms are well-designed, they must be seen as serving the people, not stalling the democratic process.

Bangladesh today stands at a democratic crossroads. The nation’s long journey through political turbulence, economic inequality, and governance challenges has created a yearning not just for change—but for participation. Elections delayed until April 2026 could erode the trust the interim government initially gained, and push an already fragile polity toward further division and disillusionment.

If the current leadership genuinely intends to guide Bangladesh toward a stronger, more democratic future, it must listen to the people. The call is not for chaos or premature action, but for a responsible and accelerated transition back to elected governance. Reforms and elections are not mutually exclusive—they must proceed in tandem.

As history has repeatedly shown, democracy delayed is democracy denied. Bangladesh cannot afford to wait.