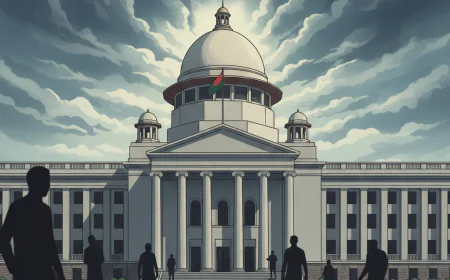

Bangladesh Women’s Commission: Between Promise and Pitfall

The proposition to establish the Bangladesh Women’s Commission has emerged as a lightning rod for public discourse, triggering a cascade of reactions across political, social, and ideological spectra. At its core, the initiative reflects an acknowledgment—long overdue—of the structural injustices faced by women in Bangladesh. It represents an attempt to institutionalize gender equity within the architecture of state governance.

Yet, amid hope and urgency, the proposal has also generated serious contention, suspicion, and resistance. As Bangladesh navigates the increasingly complex terrain of democratic accountability, gender justice, and institutional integrity, the fate of this proposed commission offers a revealing lens into the nation’s priorities and contradictions in May 2025.

The roots of this proposal lie in decades of consistent advocacy from feminist organizations, human rights defenders, and survivors of gender-based violence. It is not a spontaneous or politically manufactured whim; rather, it has emerged from the cumulative failure of existing institutions to deliver substantive justice to women across the country. Despite constitutional guarantees, Bangladesh’s legal and bureaucratic structures have been unable—or unwilling—to protect women from systemic abuse, exploitation, and exclusion.

The data underscores this crisis with grim clarity. According to the latest figures released by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics in April 2025, cases of gender-based violence have risen by 17% compared to the previous year, with rural regions showing the sharpest increases. While this spike may partially be due to greater awareness and reporting, it also reflects an unyielding culture of impunity, where perpetrators are rarely held accountable. Even more troubling is the fact that a significant portion of these crimes go unreported, buried beneath fear, familial pressure, and institutional apathy.

Compounding the problem is the fragmented and under-resourced nature of current support systems. The Ministry of Women and Children Affairs remains chronically underfunded. The National Human Rights Commission has faced repeated criticisms for its lack of proactivity. And while various civil society groups continue to fight on the ground, they lack the legislative backing and state collaboration needed for long-term impact. A national Women’s Commission, if granted full independence and effective operational capacity, could bridge these gaps—providing not just reactive justice but proactive reform, data collection, public education, and policy guidance.

However, the optimism surrounding the proposal must be tempered by a sober analysis of the political environment in which it is being introduced. Critics from opposition parties argue that the government’s sudden enthusiasm for gender justice is deeply strategic. With mounting international pressure and a desire to present itself as a modern, progressive state, the ruling party has significant incentives to champion a high-profile commission. These critics warn that the commission may be used as a political tool to control dissent, whitewash failures in governance, or even silence women activists who do not align with ruling-party narratives.

Such concerns are not entirely hypothetical. Bangladesh’s political history is replete with examples of seemingly independent bodies becoming subsumed by executive overreach. If appointments to the Women’s Commission are determined by partisan allegiance rather than expertise, it will inevitably erode public trust and compromise the commission’s moral authority. In that case, what begins as a platform for women’s empowerment could devolve into yet another bureaucratic extension of the status quo.

Resistance has also emerged from conservative and religious quarters, many of whom view the proposed commission as a threat to traditional family values and religious personal laws. These groups argue that a centralized women’s body may attempt to impose reforms that clash with cultural or faith-based practices, particularly in areas like inheritance, marriage, and dress codes. In recent months, prominent leaders from conservative networks have launched social media campaigns and grassroots mobilizations opposing the commission, framing it as a vehicle for “Western feminist ideology.” These arguments, often laced with misinformation, have gained traction in semi-urban and rural regions, where mistrust of state intervention in family matters runs deep.

While some of these concerns may be rooted in legitimate fears of cultural displacement, many also reveal the entrenched patriarchy that continues to view women’s autonomy as a destabilizing force. The challenge for policymakers, therefore, is to build a commission that protects universal rights without alienating key segments of the population. This balancing act requires inclusive consultation, transparent dialogue, and culturally sensitive but rights-anchored planning.

An additional critique comes from within the legal and institutional ecosystem itself. Lawyers, bureaucrats, and even women’s rights advocates have pointed out that Bangladesh already possesses a complex web of agencies ostensibly dedicated to gender justice. These include not just ministries and commissions, but also specialized cells within the judiciary and police. The creation of another body, they argue, could result in jurisdictional confusion, administrative redundancy, and dilution of accountability. These skeptics propose that instead of establishing a new institution, the focus should be on reforming and empowering existing ones, ensuring better coordination and funding.

This argument, while practical on the surface, overlooks the symbolic and functional value of a standalone Women’s Commission. What sets such a body apart is its ability to centralize responsibility, prioritize gender justice across sectors, and serve as a singular advocate for women within the state machinery. Redundancy is a risk only if the commission lacks a clear mandate, operational autonomy, and measurable targets. With the right framework, it could instead function as a force multiplier—synchronizing fragmented efforts, amplifying women’s voices, and holding institutions accountable through data-driven oversight.

Nonetheless, there is a real danger that the commission may become a hollow institution, mired in bureaucracy and ceremonialism. Bangladesh has seen numerous commissions and councils that began with ambitious blueprints but were eventually crippled by funding shortages, political interference, and institutional lethargy. Without strong monitoring mechanisms, transparency mandates, and civil society oversight, the Women’s Commission could be reduced to little more than a token gesture—visible in headlines but invisible in the lives of ordinary women.

This fear is already being articulated by grassroots activists across the country. In consultation sessions held in Khulna, Sylhet, and Rangamati in early 2025, women leaders voiced concerns that the proposed commission was being designed without adequate regional representation or community input. Many warned that unless the commission prioritizes intersectionality—acknowledging the unique struggles faced by indigenous women, disabled women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and economically disenfranchised groups—it risks replicating the urban, elitist biases that have long plagued policy-making in Dhaka.

The question, then, is not just whether Bangladesh needs a Women’s Commission, but what kind of commission it needs. The distinction is crucial. A top-down, donor-pleasing body with little grassroots linkage will fail to create transformative change. Conversely, a genuinely autonomous, inclusive, and technically competent commission could recalibrate the entire national conversation around gender, justice, and equality.

The potential benefits of such a body are manifold. If operationalized effectively, the commission could mainstream gender perspectives into all legislation and development plans—ensuring that economic policies, climate adaptation strategies, and education reforms do not perpetuate gender disparities. It could facilitate legal aid and psychological support for survivors of violence in remote areas, through mobile units and regional offices. It could become the national center for research on gender-based issues, producing disaggregated data that informs everything from police training to school curricula. And perhaps most importantly, it could inspire confidence among women who have been systematically marginalized—not by offering charity, but by restoring their rightful place in the justice system.

Still, implementation will make or break this vision. As of May 2025, the legislative process remains incomplete. The bill establishing the Women’s Commission is undergoing final review in parliament, with several amendments still under negotiation. Civil society groups continue to push for key provisions: mandatory representation of grassroots women in the leadership structure, transparent recruitment procedures, and budgetary independence through parliamentary approval. The outcome of these negotiations will determine whether the commission is a real institutional breakthrough or another compromised compromise.

Meanwhile, the public discourse surrounding the commission reveals something even more profound—a national reckoning with the role of women in state-building. For too long, gender issues have been relegated to secondary status, framed as social or charitable concerns rather than matters of constitutional and democratic urgency. The Women’s Commission, in its best incarnation, could reverse this trend. It could assert that women's rights are not adjuncts to development but foundational to justice, freedom, and nationhood.

The Bangladesh Women’s Commission proposal offers a rare opportunity to translate decades of advocacy into durable institutional architecture. It is a bold idea situated in a fragile environment. Its success will hinge not only on legal texts or organizational charts but on political will, public engagement, and above all, moral clarity. If built on inclusion, independence, and integrity, it could transform Bangladesh into a regional leader in gender equity. If misused or mishandled, it will become another missed opportunity, another name in the long list of promises unfulfilled.

The stakes are monumental—not just for women, but for the democratic future of the country itself.