End of Kamalapur Station’s Legacy as New Transport Hub Takes Shape

In Dhaka’s frenetic Motijheel, Kamalapur Railway Station has stood as Bangladesh’s grand gateway since 1969. Its sweeping roof, which resembles to Sydney’s Opera House and the humble Bengali thatched hut, is a beacon of architectural ingenuity and national pride.

But the station’s days are numbered. Bangladesh Railway has unveiled bold plans to demolish this historic landmark and transform it into a gleaming ‘multimodal transport hub’—a futuristic nexus of high-speed trains, metro rails, subways, and expressways. As the nation braces for this seismic shift, the question lingers: can progress honour the past while racing toward the future?

A station steeped in history

Kamalapur, opened in 1969 after a decade of planning, was a response to the limitations of Dhaka’s older Fulbaria station, built in 1885 and ill-equipped for a growing capital.

Designed by American architects Daniel H Burnham and Robert George Boughey, Kamalapur’s open-sided structure and soaring roof blended global flair with local roots.

For over five decades, it has been Bangladesh’s largest railway station, a bustling artery connecting millions to destinations nationwide. Its aesthetic simplicity – airy spaces and a curved canopy – made it an enduring symbol of Dhaka’s identity.

Yet, the demands of a modernising Bangladesh have outgrown Kamalapur’s charm. Urban congestion, environmental pressures, and the rise of diverse transport modes have prompted a radical rethink. Enter the ‘multimodal transport hub,’ a vision to integrate trains, metro rails, buses, and more under one roof, surrounded by hotels, entertainment centres, and commercial complexes. Japan’s Kajima Corporation, also tasked with transforming Dhaka’s airport station, will spearhead this ambitious overhaul.

A hub for the future

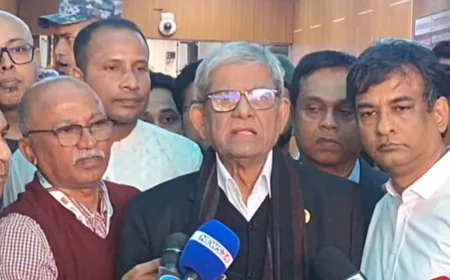

The new Kamalapur will be a marvel of connectivity. “Passengers will seamlessly travel to any part of Dhaka or beyond,” said Al Fattah Md Masudur Rahman, Additional Director General (Infrastructure) at Bangladesh Railway, while talking to Jago News. Underground tracks will ferry high-speed trains, while a multi-storey complex above will house commercial and transit facilities. The hub aims to ease road congestion and cut emissions, aligning with the government’s ‘Green Railway’ initiative, approved by ECNEC with a Tk 935.1 million budget, funded partly by a Tk 651.14 million World Bank loan.

The project, backed by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), operates under a public-private partnership (PPP). JICA’s final implementation report, due this month, will detail the blueprint. Kamalapur’s rolling stock and diesel workshop will relocate to Dhaka’s Bay Terminal, and the Narayanganj-Joydebpur and Dhaka-Chattogram routes will transition to electric trains as part of a pilot. “This isn’t just a station; it’s an integrated transport ecosystem,” Rahman enthused.

Balancing progress and preservation

The decision to demolish Kamalapur has sparked debate. Its unique design, blending global and local elements, holds cultural weight. For many, it’s more than a station – it’s a memory of departures and reunions, a testament to Bangladesh’s post-independence ambition. Critics argue that modernization could preserve the iconic structure, perhaps integrating its roof into the new hub. Others see the demolition as inevitable, given the station’s inability to handle Dhaka’s 20 million-plus residents and their transit needs.

The project’s cost, estimated at Tk 93.51 crore, of which Tk 28.37 crore would come from state coffer and the remaining Tk 65.14 crore would be borrowed from World Bank. The project’s timeline—January 2025 to December 2026—reflect the government’s urgency.

The World Bank’s involvement underscores global confidence in Bangladesh’s infrastructure push. Yet, the transition won’t be seamless. Relocating operations and ensuring minimal disruption during construction pose logistical hurdles. The involvement of Kajima, a seasoned player, offers reassurance, but public scepticism about PPP projects, often plagued by delays, lingers.

A green vision for a crowded capital

The ‘Green Railway’ ethos driving the project aligns with Bangladesh’s environmental goals. By shifting transport from roads to rails, the hub aims to curb Dhaka’s notorious traffic and pollution. Electric trains and integrated transit options promise efficiency, while commercial developments could transform Kamalapur into a vibrant economic zone. The airport station’s parallel transformation suggests a broader vision: a network of hubs knitting Bangladesh’s urban centres together.

For passengers, the benefits are tantalizing. A single hub offering metro, bus, and train connections could slash travel times and costs. Imagine stepping off a high-speed train from Chattogram, hopping onto a metro to Gulshan, and grabbing dinner at a station hotel – all without braving Dhaka’s gridlock. Yet, the loss of Kamalapur’s open-air charm, where vendors and travellers mingled under its vast roof, tugs at the heartstrings.

The road ahead

As bulldozers loom, Kamalapur’s fate mirrors Bangladesh’s broader crossroads: tradition versus transformation. The multimodal hub, with its promise of connectivity and sustainability, could propel Dhaka into a new era. But the erasure of a cultural landmark risks alienating those who see Kamalapur as more than bricks and mortar. Can the new hub capture its predecessor’s spirit while meeting 21st-century demands? As JICA finalises its report and construction looms, Bangladesh holds its breath, awaiting a future that honours both its past and its ambitions.