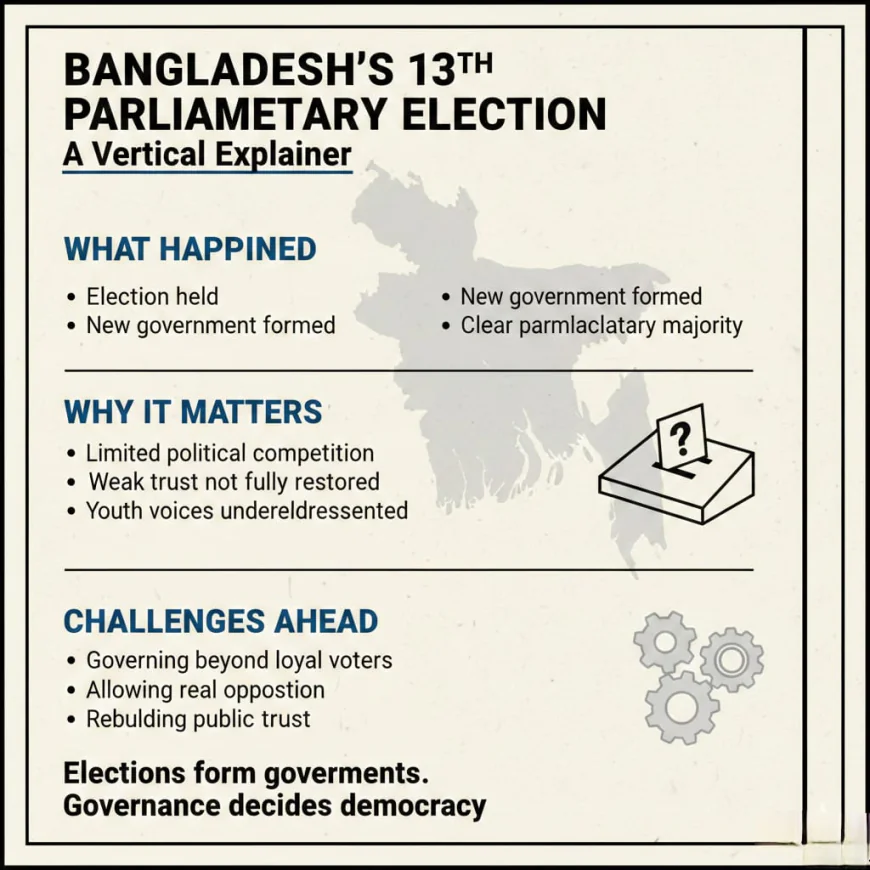

Bangladesh’s 13th Parliamentary Election: Power Secured, Trust Still Pending

The 13th parliamentary election in Bangladesh has delivered what the state urgently needed: a constitutionally formed government and a clear numerical mandate. What it has not yet delivered is democratic comfort. And that distinction matters more than many would like to admit.

This election was never meant to be routine. It came after a prolonged period of political tension, mass mobilisations, institutional strain, and public fatigue with cyclical instability. In that context, the ballot was not merely a mechanism for choosing a government—it was a referendum on whether Bangladesh’s democratic framework could restore public confidence while preserving state continuity. The result answered the first question decisively. It left the second unresolved.

The winning party now commands overwhelming parliamentary dominance. From a governance standpoint, this creates short-term stability and administrative clarity. Legislation will move smoothly, budgets will pass without gridlock, and executive authority will face little resistance. For a developing state navigating economic pressure and geopolitical scrutiny, such decisiveness can appear attractive.

But democracies are not sustained by efficiency alone. They endure through legitimacy—and legitimacy is not derived solely from seat counts.

The broader concern emerging from the election lies not in legality, but in participation and representation. A parliament that lacks ideological diversity, robust opposition, and competitive tension risks becoming procedurally functional yet politically hollow. When electoral victory is not matched by inclusive political engagement, governance becomes insulated, and insulation breeds disconnect.

This is where the real test for the new government begins.

One of the most pressing challenges ahead is rebuilding political trust beyond its core support base. Elections can close chapters, but they do not automatically heal fractures. A significant segment of society remains sceptical—not necessarily hostile, but unconvinced that electoral politics meaningfully reflects their voice. Ignoring this sentiment would be a strategic miscalculation. History, both within Bangladesh and beyond, shows that democratic erosion often begins not with coups, but with apathy.

Equally critical is the condition of opposition politics. A weak or marginalised opposition does not strengthen the ruling party; it weakens the state. Parliaments function best when dissent is institutionalised, not suppressed or rendered symbolic. Without credible opposition, accountability shifts from public debate to internal discretion—a dangerous transition in any democracy.

The election also exposed a structural dilemma involving youth participation. Young citizens played a visible role in recent political movements, yet that energy did not translate proportionally into electoral representation. This gap signals a deeper issue: existing political structures are failing to absorb new political aspirations. If left unaddressed, this disconnect risks pushing political engagement outside institutional boundaries—where it becomes volatile rather than constructive.

Another challenge lies in governance behaviour after victory. Democratic legitimacy is not secured on election day; it is earned daily through restraint, transparency, and respect for dissent. How the government treats criticism, the media, civil society, and independent institutions will determine whether this election is remembered as a turning point or merely a reset.

The temptation for any dominant government is to confuse mandate with entitlement. That temptation must be resisted. Power exercised without dialogue may be legal, but it is rarely sustainable.

There is still a path forward—one that transforms electoral dominance into democratic leadership. It requires deliberate political inclusion, structured dialogue with opposition forces, protection of institutional autonomy, and a clear signal that dissent is not a threat to the state but a component of its resilience.

For the international community, the message is equally nuanced. Bangladesh has demonstrated state continuity and administrative control. What remains to be seen is whether it can now demonstrate democratic maturity—by governing not only for those who voted, but also for those who doubt.

The 13th parliamentary election has given Bangladesh a government. The coming years will determine whether it also strengthens democracy. In the end, the durability of the state will depend less on how power was won, and more on how it is exercised.